“No climber ever expects to be in this position. When I was planning Lhotse, the word “earthquake” never entered my mind.” From Alan Arnette’s blog.

I’ve been on Everest four times, and on Lhotse once. During all those expeditions, the risk of earthquake never once occurred to me or my companions. I’m not sure what the risk management strategy would be. Run away? You aren’t going to get far.

This powerful video of the avalanche that was triggered by Nepal’s 7.8 magnitude earthquake and struck Everest base camp shows just how futile running away would be.

Last August I was ski-touring in the lakes region of northern Patagonia. The last summit of our trip was the iconic volcano of Orsono, and to the south of us lay another pretty volcano with its skirts of deep green forest and shirt of pristine white snow – Chalbuco.

After decades of inactivity, with no warning noticed by local monitors, Chalbuco erupted twice on 22-23 April of this year, sending a huge column of lava and ash several kilometres into the air and causing the authorities to declare a red alert and evacuate more than 4,000 people.

Left: my photo of Chalbuco from Osorno. Right: A APF/Getty image of Chalbuco erupting, with Osorno visible on the left.

Dave and I knew we were skiing on live volcanoes. One village we departed from had volcano evacuation route signs prominently displayed. We laughed and photographed them and kept going. What to do if the thing actually erupted never featured in our safety plans. I guess we assumed someone somewhere with some authority would have some idea it was coming and warn us off.

Beyond that we’d take our chances. As individual adventurers heading into environments encompassing a range of risks, the best we can do is have a general safety plan in place – for medical treatment, for communication, for evacuation – a plan that hopefully covers any of the many ways in which adventure can go wrong, even the ones we haven’t thought of.

Volcano eruption evacuation routes marked at the village entrance.

The safety conscious might wag their fingers and say we should have stayed at home. (And indeed, on Alan’s blog is a long debate on whether the climbers on Everest ‘deserved’ helicopter evacuation after the earthquake – a debate so mired in colonialism and white guilt and first world wealth and commercial-vs-‘real’-climber judgements that it’s hard to pick your way through it.)

But how safe is it at home?

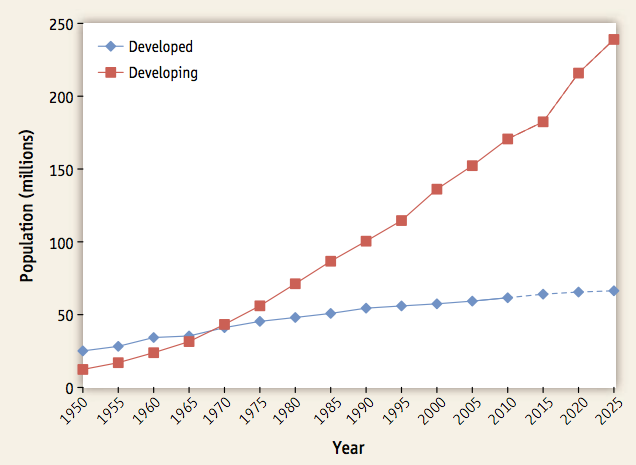

How many people do you think live within 100 kilometres of a fault capable of generating a magnitude-7 (or stronger) earthquake? (To give scale to this, Everest was about 160 km from the epicentre of Nepal’s earthquake.)

The answer is an astonishing 250 million people.

The plot shows the total population since 1950 of “developing” and “developed” cities that are located within 100 km of a fault capable of generating an earthquake with M ≥7. (Tucker 2013). Sourced from VOX http://www.vox.com/2015/4/27/8501281/earthquake-risk

And if this is the reality of your home, then risk management needs to be handled much more specifically.

It was no secret that Nepal was ill-prepared. It was known the most buildings would not withstand an earthquake, indeed most of them didn’t even comply with the building code that Nepal did have in place. It was known that Nepal lacked a disaster protocol. A week before the earthquake some 50 experts assembled in Nepal to discuss just these problems.

It is an axiom of earthquake management that (the odd avalanche aside) earthquakes don’t kill people, buildings kill people. In 2010 two similar earthquakes hit Chile and Haiti. “Only about 0.1 percent of Chileans affected by the 8.8-magnitude earthquake died. By contrast, 11 percent of Haitians affected by a 7.0-magnitude earthquake with similar shaking died.”

Why? Because the 9.5-magnitude earthquake that struck Chile in 1960 had left earthquake-preparedness front and centre in national and government consciousness.

What is it about earthquakes that leads mankind to often ignore this particular risk? It seems to be more than just rarity – earthquakes are actually fairly common and are visually dramatic, so they tend to feature in the world-wide news cycle. From 2000 to 2010 there were 22 earthquakes of magnitude 6 or greater.

In 2013 Brian Tucker, founder of GeoHazards International, published an important paper about this in Science. His paper is subscription only but VOX picked out some of his key ideas.

Often, Tucker points out, it’s a funding problem, particularly for poorer countries. Upgrading buildings is expensive, after all. In some cases, there might be unique obstacles at work (in Nepal, civil unrest made the task of retrofitting even harder). But in many areas, the biggest barriers appear to be psychological — people aren’t even thinking about preparing for earthquakes.

“The psychological reasons we don’t prepare for earthquakes are often ignored,” says Tucker. “Just as an example, we still find a lot of people who think of earthquakes solely as an act of God, and don’t think about the very real ways to reduce risks.”

I’m a believer in ‘acts of God’, in the sense that I think we are too quick to assume that every accident must be blamed on someone and that every risk must be avoidable. As individual adventurers passing for short periods through high risk environments, I feel a general protocol for disaster preparedness is the best we can do. Nevertheless, just researching this post has challenged my own assumptions about risk preparedness.

Individual adventurers aside, as societies permanently settled in risky environments, with access to both information and solutions, we can and must do better in protecting ourselves and our citizens.

Support MITRA Music for Nepal, my initiative with Anni Hogan to raise funds for reconstruction in Nepal.

Like us on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/MitraMusicForNepal and follow us on Twitter @Music4Nepal