Key moments in the journey of life.

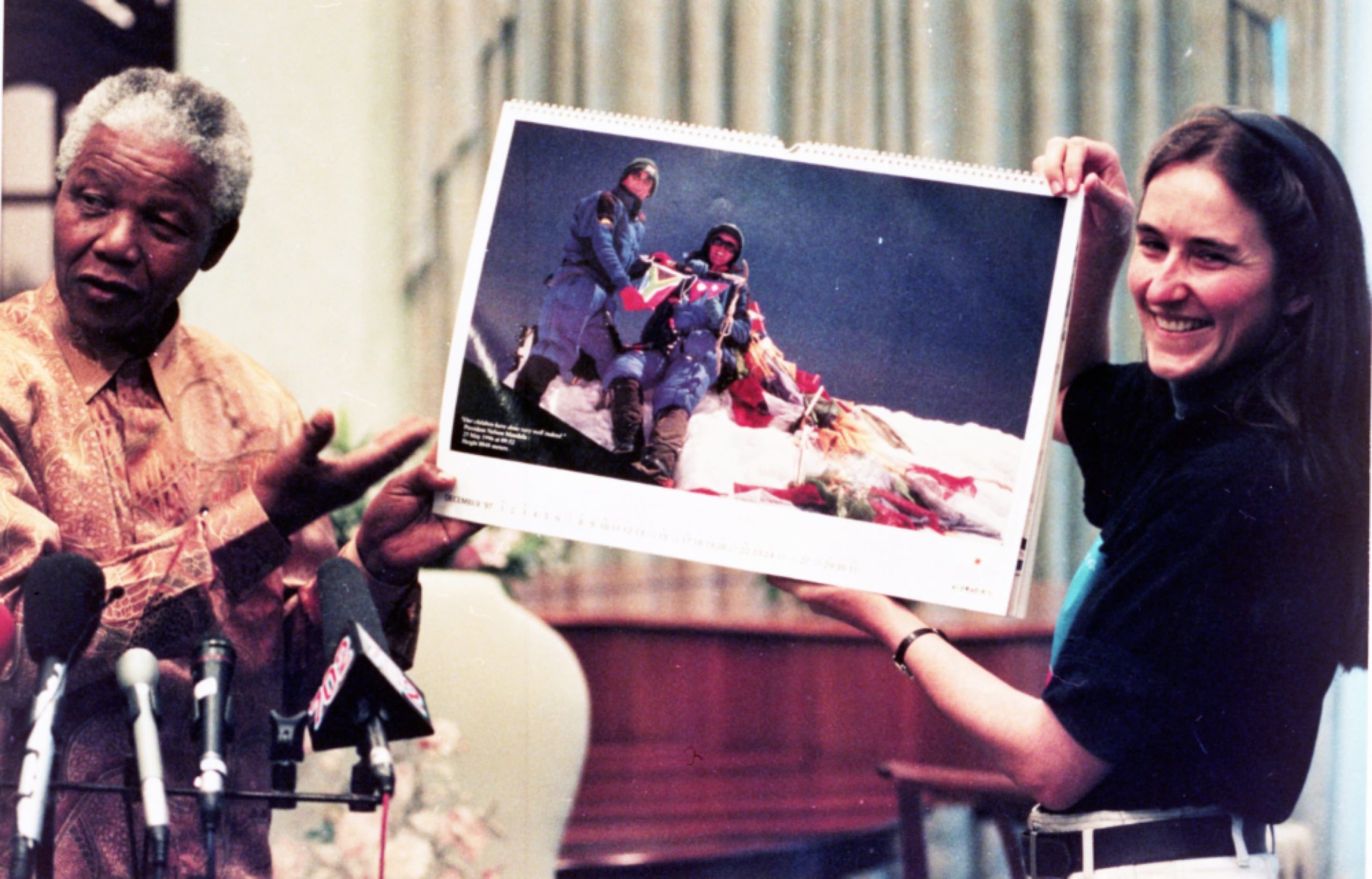

Looking back at the course of a lifetime, there are certain moments where, if you’d made a different choice, you’d be living a completely different life. Given how experiences shape character, you’d probably be a different person. It’s twenty years since I became the first South African to climb Everest, but that epic, complex, controversial journey didn’t begin in Nepal. It began on the slopes of Kilimanjaro. And it began with one of those key moments.

I was 26 years old, living in sleepy university town of Grahamstown in South Africa, in theory working on my masters thesis but actually lying on the carpet on a sunny Sunday morning, reading the newspaper. A front page article caught my attention.

‘Sunday Times Everest Expedition. We take the South African flag to the top of the world’.

Under it was a picture of three men standing on top of Table Mountain, the most famous mountain in the country, all of 1,000 metres high.

It was the third paragraph that jumped out and grabbed me by the throat: ‘The other male members have been selected, but Woodall is still looking for a South African woman climber.’

South African. Woman. Climber. I was all of those things. But Everest?

I’d been rock-climbing since I was eighteen, I’d gone mountaineering in the Rwenzori, Bolivia and the Alps, but it had never occurred to me to consider Everest. It seemed much too high, too hard, utterly out-of-reach for the likes of me. Nevertheless, ever since I’d read my first book about mountaineering, I’d hoped one day to see the Himalaya. That book was Annapurna: a woman’s place, by Arlene Blum (I highly recommend it). It was the story of the first all-woman expedition to the Himalaya, their cheeky (for the 1970s) motto was A woman’s place is on top.

The newspaper article explained that interested women needed to send a written motivation. The team leader would draw up a short-list of six and take them on an expedition to Kilimanjaro, Africa’s highest mountain. One would then be invited to join the Everest team.

Cathy on the summit plateau of Kilimanjaro.

I could think of a thousand reasons not to apply. I wasn’t experienced enough. I wouldn’t be chosen. It was a publicity stunt. It was sexist to invite the men but put the women through selection. I could think of a thousand reasons to apply. I was one of the most experienced women climbers in South Africa. I might well be chosen. Who cared if it was sexist? And I would get a free trip to Kilimanjaro. In the end, one reason prevailed over all others.

If I didn’t apply, another woman would go and for the rest of my life I would wonder:

Could that have been me? What might have been?

I agonised for over a week over my application. It felt intensely difficult to express all of myself in a few pages of black-and-white text. I was one of over 200 women who took the plunge and applied.

Much later I would read the remainder of those letters. Most were not from young adventurers but from women in early middle age. A common thread ran through many of them. These women filled their roles in life well. They were good wives, mothers, employees. Many were clearly outstanding at what they did. Yet there was an unspoken question shining through all their applications: Was this all there was to life? There was a yearning to do something more, something just for themselves.

It was three long weeks before I heard that I was on the short-list. Soon thereafter I was on a plane to Tanzania, one of six women, being assessed by a male team leader, and observed by a male journalist and a two-man TV crew. It was an odd dynamic and a very early example of what we now call reality television. But that was before anyone realised these sort of experiences could lead to media careers. We were there with eyes firmly focused on mountain summits.

Despite the many differences, I could see a common trait in all the women – a determination and focus that we applied to whatever dominated our lives. Where a similar group of men might have been more inclined to posture, to try and top each other with stories of how far they’d run or how high they’d climbed, we pulled together as a group. Nevertheless, under all that lay an intensely competitive spirit. For the team leader this might be a selection, but for us it was competition. All of us desperately wanted to go.

The hardest part was that the leader made it clear he was not looking for the most experienced person. He wanted compatibility, mental strength, determination. He told us just to be ourselves. That left me with the horrible thought: What if being myself was simply not good enough?

The six women looking less than happy at the foot of Kilimanjaro, as the expedition is about to set out.

The expedition began with an ascent of Mount Meru. The mountain was in a setting more reminiscent of Hollywood Africa than real Africa, rising out of a deep green tropical forest surrounded by green grassland dotted with small trees and grazing giraffes. Two magnificent rock ridges formed a horseshoe of huge cliffs, encircling what remained of an ancient volcanic crater.

From the peak we had a magnificent view of Kilimanjaro on the horizon to the east, a great swelling rising out of the plateau. Across its broad summit lay a mantle of snow and glacier. It seemed to float above the heat haze, an unlikely vision rising above tropical Africa. I could imagine no better place to be at dawn on New Year’s Day, 1996.

Kilimanjaro was a longer, more complex challenge than Meru. A dirt road led us past giant banana palms and tiny houses, before turning into mud as we vanished into lush forest, very green and very wet. One of the fascinations of the mountain is the many climatic zones. We emerged from the clammy jungle heat into the heather belt, climbing up through a landscape of rock and moss slopes. Days of mist teased us with brief glimpses of huge rocky peaks hovering in banks of cloud. Clear nights found us huddled around a campfire, telling jokes under a vast black sky studded with stars.

The landscape was a delight but the process of being ‘on selection’ was not. As we all became more used to the expedition conditions, the group became less cohesive and the strain began to tell. The leader made it clear he expected some of us would withdraw from selection. Through the pleasant days of hiking, I couldn’t imagine giving up. I felt very differently on the summit night. We left camp at about 1 a.m., stumbling up loose scree slopes through the long, dark hours of early morning. It was a relentless steep slog and I was sliding downwards with each step on the broken rock. Exhausted, freezing cold and demoralised, I was desperate to stop and rest. Sadly, the only way to keep warm was to keep moving.

Somewhere in those long icy hours, when it seemed as if the sun would never rise again, I decided to withdraw from selection. If Kilimanjaro was this unpleasant, Everest had to be far worse. Without enjoyment, I couldn’t see the point of it all. Then the first glimmer of dawn appeared, a slim line of red on the horizon. Slowly a golden glow crept up the eastern sky. As it grew so did my energy. All thoughts of giving up slipped away with the retreating darkness.

I worked my way around the crater rim, past the great slabs of glacier, lying on the rock like massive chunks of wedding cake. I pulled my down jacket tightly around me as protection against the howling wind. At 5.17 a.m. I finally stood on the summit of the African continent.

The six women on the summit of Kilimanjaro.

Could the next summit possibly be Everest?

Back in the garden of the hotel, we prepared for the final decision. There was a kind of tense camaraderie among us as we waited. As befitted reality TV, the whole process was drawn out until I felt like a piece of putty that had been stretched far too thin. I thought I was the best choice and that I had a good chance. But I didn’t want to be too confident for fear of being wrong. As the tension mounted, I desperately wanted to be selected.

Finally, finally, the leader made his announcement. He was inviting two women to come to Nepal on the three week trek to base camp. Only at base camp would one of the two finally be selected to go onto the climbing permit. I got one invitation. Deshun Deysel, a young PE teacher from a coloured township, got the other.

My dream had come true. I was going to the Himalaya! But I still didn’t know if I was going to climb on Everest.

Originally published on the Kandoo Adventures blog.