Most people I meet assume that Everest must have been childhood dream and my first Everest trip the culmination of years of planning. In fact it really hadn’t occurred to me until I picked up a newspaper in November of 1995 and saw a story about the 1st South African Everest Expedition.

Four months later I was on my way for an experience that would change the course of my life…

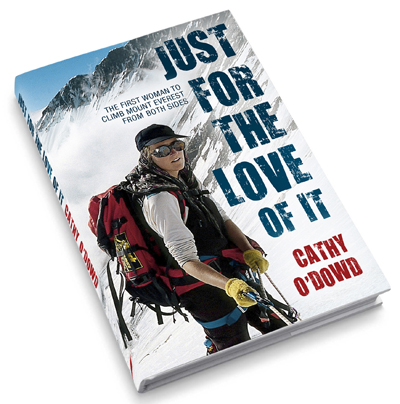

The following is the prologue of my book, Just for the love of it, which tells the story of my four expeditions to Everest, of which the First South African Everest Expedition was the first.

I dumped the Sunday paper on the table and went into the kitchen to make myself coffee. I had promised myself a leisurely start to the day before getting back to work writing up my Masters thesis. I would sit in the sun, which was streaming in through the bay windows, read the paper, and then return to my computer. I would rather have spent the day rock-climbing, but it was November, time of end-of-year exams, and there was no one available to join me on the rock.

I lived in Grahamstown, a small town hanging onto vestiges of its British past in the middle of the great sun-baked plains of the Eastern Cape in South Africa. The town centred on a university and a few elite schools. I had been in Grahamstown for nearly three years and was in the final months of my Masters degree in Media Studies.

I was a Johannesburg girl, born and bred in the great city where all South Africa’s wealth and industry is concentrated. Johannesburg is not a pretty city, nor a very safe one, but it was vibrant. I found the isolated, small-town atmosphere of Grahamstown alternately soothing and stifling.

As I spread the newspaper on the table I cast my eye over the headlines. One struck me immediately: ‘Sunday Times Everest Expedition. We take the South African flag to the top of the world’. Under it was a picture of three men standing on top of Table Mountain. Table Mountain is South Africa’s pride and joy, all of 1 000 metres high. It was going to be quite a leap from there to 8 848 metres, the summit of the world. I read on, most interested.

I had been rock-climbing for nine years, ever since leaving school, and I was passionate about the sport. For six of those years, I had also been mountaineering, a sport more difficult to indulge in as a South African. The highest mountain at our end of the African continent is Thabana Ntlenyana, which, being all of 3 482 metres high, receives little more than a smattering of snow each year. I had travelled to the Ruwenzori in Central Africa, to the Bolivian Andes, to the Alps. However, the man I had done most of my mountaineering with had been killed in Peru 18 months previously, and I had done nothing since then.

The Sunday Times team was to attempt the classic south route up Everest in May of 1996. It would be the first ever attempt by South Africans. Before the fall of apartheid, we had not been able to get permits for the world’s biggest mountains. The expedition leader was Ian Woodall. I had never heard of him. I looked at his photograph – dark-blonde curly hair, small in stature, in his late thirties or early forties. It made little impression on me. Then the third paragraph jumped out and almost grabbed me by the throat.

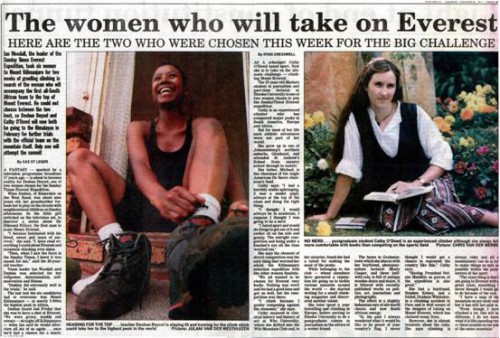

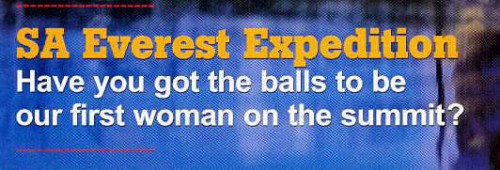

‘The other male members have been selected, but Woodall is still looking for a South African woman climber.’ Women who were interested were asked to send in a written motivation. A short-list of six would be drawn up, and they would accompany Ian on an expedition to Kilimanjaro, Africa’s highest mountain. One would then be invited to join the Everest team.

One of the ‘advertisements’ run to promote the search for a woman to join the Everest team.

The climbing of Everest had never entered my mind before. It was not a childhood dream, not a life-long ambition. If I had ever thought of it, I had dismissed the idea instantly, as Everest was too big, too far away, too expensive. However, I certainly was desperate to visit the Himalaya. I had been looking around for ways of doing that for over a year.

My first thought was that the woman thing was a sham, a publicity stunt drummed up by the newspaper. I started phoning around until I found someone with a telephone number for Ian. I rang the number and got him on the other end. It was a confident, precise voice, giving nothing away. He assured me the selection was ‘for real’.

‘You are not going to have us in bikinis at Sun City, parading for the television cameras?’

He laughed. ‘That sounds like a good idea. But no, all I want is your application and motivation.’

He would tell me nothing more. I put down the phone and began to walk distractedly through my flat. I could think of a thousand reasons not to apply. I wasn’t experienced enough. I wouldn’t be chosen, anyway. It was a publicity stunt. It was sexist to select the women and invite the men.

I could think of a thousand reasons to apply. I was one of the most experienced women climbers in South Africa. I might well be chosen. Who cared if it was sexist? It would be worth it just to get to the Himalaya. It would be worth it for a free trip to Kilimanjaro. The application required no more effort than writing a motivation, and posting it.

One reason prevailed over all others. If I did not apply, for the rest of my life I would wonder what would have happened if I had done so. Another woman would go and I would be thinking, could that have been me? What might have been?

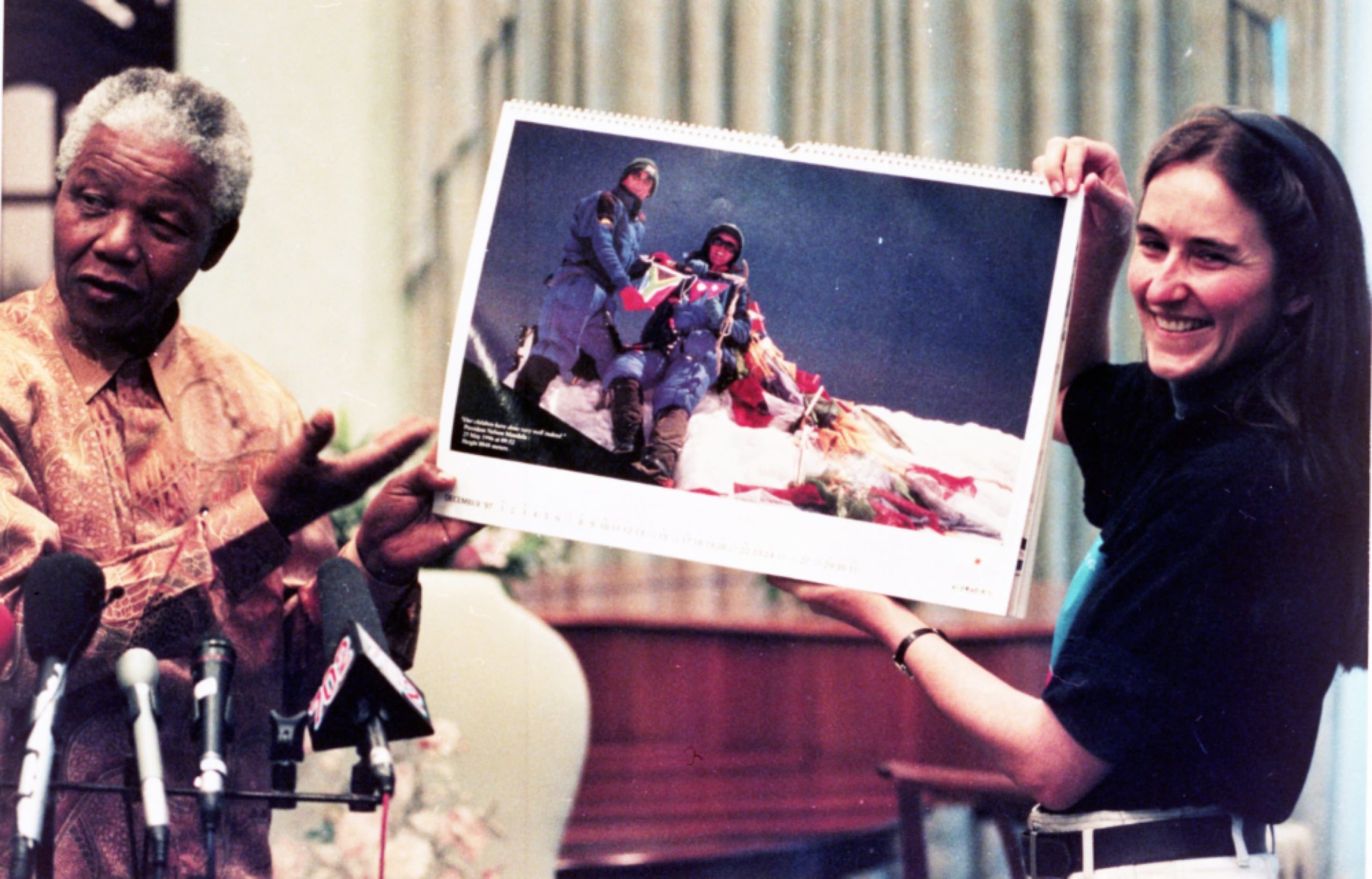

This book is the story of what happened because I chose to apply. Within the next three-and-a-half years I was to become the first woman in the world to climb Everest from both its south and north sides. I was to encounter death on the mountain in its most traumatic forms. I was to become both famous and notorious in South Africa and beyond. I was to give up my planned career as an academic to go into expedition and adventure work full-time. I was to fall in love with the expedition leader. And it was all for the sake of one decision on 19 November 1995.