This article appeared in edited form in the Mountain Club of South Africa Journal 1999.

24 May 1998

We had been climbing since 2.30 a.m., picking our way up the rock-and-snow slopes of the north face of Everest, the six tiny yellow bubble of our headtorches the only light in a coal-black night. The dawn brought light but also wind. The snow along the ridge turned golden before my feet, but it was the coldest gold I had ever seen. The temperature dropped steadily.

Ahead of me a great heaped mass of rock squatted in our path – the First Step, 8 600 metres. It was 5 a.m. Blotches of colour caught my eye – a body with a purple jacket and red boots. And then the body jerked, like a puppet being pulled savagely by its strings. I walked gingerly across the loose shale. Long brown hair lay over the face and I brushed it gently aside.

‘Don’t leave me,’ she said.

Her face had the waxy perfection of Sleeping Beauty, milky white and totally smooth. It was severe frostbite but made her look like a porcelain doll. Her eyes stared up at me, the pupils huge dark voids.

‘Why are you doing this to me?’ The question seemed to be asked of life itself. Why, indeed?

She was as helpless as a rag doll. As Ian tried to get her arms into the sleeves of her jacket, she gave no resistance, no assistance. He and Jangbu then battled to pull her into a sitting position. The two strong men were doubled over, gasping for breath. To carry her down more than 3000 vertical metres of mountain was beyond our means.

‘I am an American.’

Could she be Fran, the bubbly American woman who had sat in our ABC tent one night, waiting for her husband, the Russian climber, Serguei. They were climbing as a twosome, no Sherpas, no oxygen, no radios. We found out later that she had been lying there for two nights already.

Ian had her by both shoulders, his face only inches from hers.

‘You have to help us. If you don’t, you are going to die.’

Although she was aware that we were there, she did not understand what was said to her, and she herself could only say her three phrases. It was difficult to know what was left in her head.

I noticed her crampon lying a few feet below us. I took a tentative step down the slope, a slope covered in loose rock shards, like a million smashed dinner plates, slipping away under my feet towards the Rongbuk glacier. A climber, having once lost his balance, would not be able to stop the downward momentum. Was that what had happened to Serguei?

We had been with Fran for nearly an hour, standing in temperatures around -30° C. My fingers were totally numb and my body shaking. The strangest sensation, though, came from my chest cavity. There were grey lumps floating inside it, cold lumps. It was time to move.

The decision to leave her came upon us without much discussion. But which way to go? The thought of going on was intolerable. I had passed bodies, I had had friends not come back, but I had never watched anyone die. I could not push Fran to one side, mentally, and find again my drive for the top.

So we turned away from the north ridge of Everest, from seven weeks of climbing, months of planning, thousands of dollars of sponsors’ money spent. And went home.

Our 1999 expedition to the north ridge of Mount Everest was borne out of the 1998 one. We had come so close. The technical difficulties, although greater than the south side, had not proved overwhelming. Most importantly the climbing was stunning, beautiful, exposed, challenging, interesting.

On 1 May 1999 we were back at base camp, the last of the spring season expeditions to arrive. A lot of teams arrive too early, burning themselves out before the good weather of late May. However 1 May was late. It had taken us that long to scrape the money together.

The team was a small one. Going for the summit were myself and Ian Woodall, Pemba Sherpa and Jangbu Sherpa. The two sherpas were on their third Everest expedition with us. In reserve was ABC cook and support climber Phuri Sherpa.

We spent the first two weeks acclimatizing on the Rongbuk glaciers while taking a group of South African trekkers up to 6 000 metres. The upper reaches of the east Rongbuk glacier are particularly beautiful. We walked along a tongue of moraine that ran between two seas of ice pinnacles. They rose 20 or 30 feet above us, an angry ocean frozen mid-storm. Their surfaces were pure white, the icy cracks that led into their hearts lapis lazuli.

And during that time the mountain claimed its first victim.

On 8 May the Ukrainians reached the top. Conditions were perfect and every team on the mountain would have swopped places with them just then. But the weather changed, leaving them struggling down the treacherous summit ridge through the night. One died and one was stranded with severe frostbite. A team of sherpas from various expeditions reached him that day and brought him down through the night. We passed him on the glacier, being carried by yak-herders, his nose pitch-black, hands wrapped in down gloves, eyes glazed and exhausted. But he would live.

On 18 May we moved to ABC (advanced base camp) where we would stay for the rest of the expedition. At 6500m we were now camped half a kilometre higher than the summit of Kilimanjaro. The next day we heard of two more deaths on the North side. A Belgian and a Polish team had topped out in the late afternoon in indifferent weather. The next morning one was seen to fall by the Italian team, and another was missing. Two others had frostbite.

As I lay awake with high-altitude insomnia I wondered why I was doing this. Why put up with the discomfort and the risk? I had already climbed Everest. And climbing any mountain is not the most logical activity in the world. You just end up back where you started – at the bottom. But when I sat in my tent door, wrapped in my down jacket, and watched the mountain turning deep pink as the sun set, the golden clouds drifting past, the deep blue shadow creeping up its sides, I remembered why I do this.

On 20 May Ian and I did a daytrip to 7 000 metres and camp 1. An hour’s walk brought us to the foot of the face. In 1998 the route up this had been easy, a great curve right and traverse back left. Now a giant crevasse blocked that path. The fixed line went straight up steep snow slopes and sections of 70 degree ice. Through the whole of April there was no snowfall on Everest, but we had had several storms recently. The result was soft powder snow over glass-hard ice. But worst were the temperatures. The previous night it had been -9C inside my tent. Now my thermometer was reading 41C. There was not a breath of wind, not a wisp of cloud to cast any shade. Every inch of the terrain was snow-covered, reflecting the sunlight back. I spent the next day prostrate at ABC recovering from heat exhaustion.

Other teams were on the move for the summit. We were keen to stay away from them, to avoid bottle-necking on the summit ridge. So we waited, day by day. On 25 May we climbed back to camp 1, this time for good. The camp was situated on a narrow snow platform, sheltering from wind behind a giant snow wall. All the teams left were clustered there, a multi-coloured squatters’ camp. We spent one acclimatization day there, another unbearably hot day.

Luckily 27 May was overcast, with light snowfall. We plodded up the long snow slope that makes up the lower half of the north ridge. It was not difficult, just desperately exhausting, with each breath containing that much less oxygen. Camp 2, at 7600m, is spectacular. It clings to the last snow before the rock starts and it looks north-west, with a wild view that encompasses Pumori, the central Rongbuk glacier, and in the distance Cho Oyu (6th highest in the world). In 1998 we were pinned down here for 36 hours by brutal winds, winds that knocked me to my knees when I tried to move around outside. But now the weather was benign.

The next morning we pushed on up the rock ridge and at 7900m we turned onto the north face, traversing diagonally up the fields of snow and ribs of rock. By now I was using oxygen and I could feel the difference it makes. My breathing was slower and steadier, and I no longer felt on the edge of exhaustion all the time. We were climbing at the top edge of cloud extending across Tibet. Sometimes it dipped below me, and became a beautiful fluffy blanket bathed in sunshine. Sometimes it rose up and enveloped me, becoming grey, windy and full of wet snow that kept dribbling down the collar of my jacket.

Camp 3, set at 8 300 metres, clung precariously to the side of the north face. It is the highest regularly used camp in the world, with only five mountain tops higher. The alarm was set for 11 p.m. but I was already awake, listening to the silence, Chomolungma’s blessing, for it meant no wind, stable weather and relative warmth. I had had just four hours sleep. I had barely eaten since leaving Camp 1. Now was the time to dig deep into the reserves.

It was a spectacular night, at –17C warm, with a full moon and no clouds. Hundreds of snowy mountains below us were glistening in the moonlight. We left at 12.30 a.m. and by 2.30 a.m. we were on the summit ridge. The night was silent except for the crunch of snow under my feet and the rasp of breath through the oxygen mask. The north face of Everest makes for a climb of half a world. Now, through breaks in the summit ridge cornices I caught glimpses of the hidden world east of us. On my right was the great falling sweep of the Kangshung Face, grey-sliver, topped by the snowy line of the south-east ridge, which we had climbed three years and four days previously. Behind it lurked the rocky crest of Lhotse, the fourth highest mountain in the world. To the left was the somber pyramid of Makalu, fifth highest.

Burnished gold, the moon sank into the low cloud in the west, just before the sun came up, flaming orange, in the east. It was a magical moment. The narrow north-east ridge of Everest ran between the two, with nothing but voids of air all around it. In the subdued pre-dawn light, it felt like a highway in the sky. Such moments are unforgettable, unrepeatable, the priceless reward for all the effort involved in getting there.

Ahead loomed the Second Step, a brooding mass of rock. The lower section was steep, awkward climbing up cracks. Then a ledge provided respite before the famous ladder placed there on the first ascent by the Chinese in 1960. The ladder sounds like a good idea, but proved almost more trouble than it’s worth. It is too short by a few feet, leaving one to do a desperate lunge to the right, to mantelshelf up onto a ledge.

It proved a lot further from the Second Step to the summit than I anticipated. There was a final unexpected, unnamed rock face that forms the apex of the triangle of the north face. Below my feet the face sloped down steeply for nearly four kilometres, to the Central Rongbuk Glacier – the ultimate exposure. I could now see beyond Cho Oyu, to where Shishapangma lay on the horizon.

I crested a small rise and a curved line of footprints, left by teams from the three previous days, ran like a confetti trail to the top. The summit sloped off gently to the right, in a vertical drop to the left. I began the final steps…

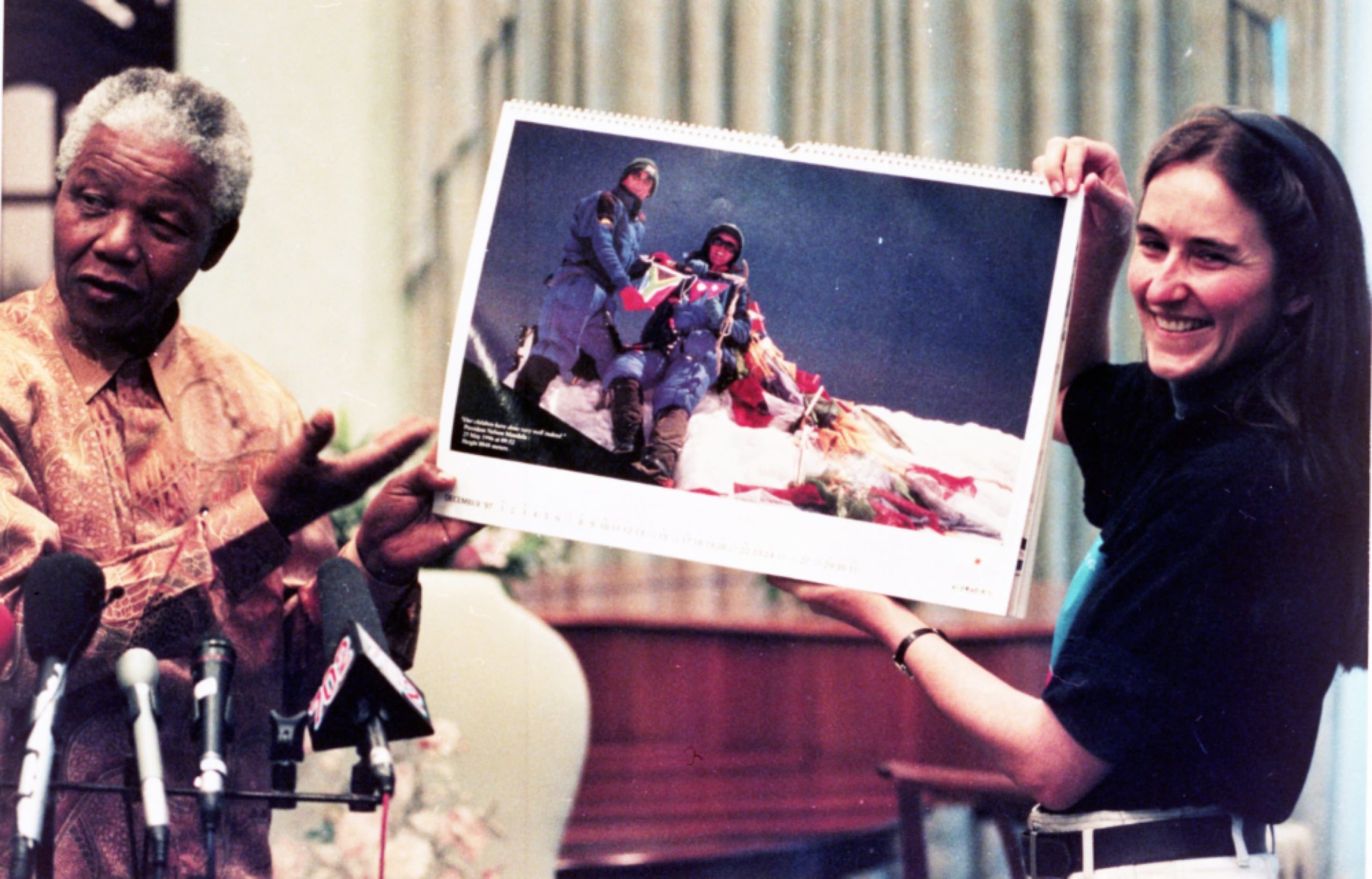

At 8 a.m. I joined Jangbu on the summit – a fast ascent. We were immediately hit by a cold wind from the south. Pemba joined us, already chattering on the radio to our ABC and base camp. Then Ian came up.

The sky arced above us, blue and clear. Cloud filled all the valleys but the mountain peaks rose out of them, like islands in a white sea. The horizon curved away in every direction. The world is a ball and we were standing on its outermost point.

I had hoped that this second time to the top of the world I would be able to sit down for a while and soak up the feeling of just being there. Because there isn’t going to be a third time. But in the end it was too cold.

In some senses the summit was, perhaps inevitably, an anticlimax. There was less of the incoherent wonder of my 1996 summit, less of the incredible celebration at base camp and at home. Once I had left camp 3 and seen how good the weather was, I was confident of reaching the top. But that had its own virtues. In place of wonder was confidence and experience. The 1996 expedition had dropped out of the sky, a miraculous gift. This one had been my expedition from first conception to this summit, the culmination of two years of work, of planning, of training, of climbing, of just keeping on trying. That was a greater summit than the pile of snow that lay on top of the mountain.

And then just when it should all have been easy, it got bloody difficult. Our descent was slow but safe, and we reached camp 3 at 1 p.m. We packed up and by 2 p.m. were moving again. Then the good weather ended. Abruptly.

First came the snow and then came the wind. The scree of the rock ridge formed an icy skin over damp ground. The safety rope was frozen, at times with a shell of ice over it thicker than the rope itself. I fell often, struggling back onto my knees only to be knocked sideways by a brutal surge of wind. I measured winds gusting up to 86 kilometres per hour, and a wind-chill temperature of -40C.

I made camp 2 at 6 p.m., frozen, exhausted, the nasty end to 18 hours of climbing. Ian stumbled in after me. We were too tired to eat or drink. Besides, the stoves were frozen solid. We collapsed into our bags and slept like the dead.

By the end of the spring season of 1996 there had been 835 ascents of Everest and I was the 39th woman ever to have reached the summit. By the time we drove away in 1999 there had been 1 173 ascents and 52 women had reached the highest point in the world. But the summit of Everest from both the south and the north – I was first woman ever to achieve that.

That record is something special, something fun to have achieved, but it occurred by accident. What I have that I cherish most is three-and-a-half years of life lived to the full, of memories, of experiences, of knowledge of the world and of myself. I remember sunrises, special vistas, moments of laughter, more clearly than I do the summits.

This article appeared in edited form in the Mountain Club of South Africa Journal 1999.