One of the questions I am most commonly asked is: what did it feel like to stand on the summit of Everest? The text below comes from my book Just for the love of it and describes my first Everest summit on 25 May 1996.

I moved slowly up yet another small rise and onto the top of it. And stopped short, aware of two figures and a sudden blaze of colour. Ian and Pemba were seated in the snow with something behind them that to my puzzled gaze looked rather like a ruined tent. After hours in an almost monochrome world of blue sky, white snow and black rock, the medley of red, yellow and green was disconcerting. Then Pemba turned and saw me. A huge grin spread across his face and I noticed his gold tooth glinting in the sunlight. He stood up and began to wave both arms and his ice-axe in the air.

Pemba Sherpa on the summit of Everest.

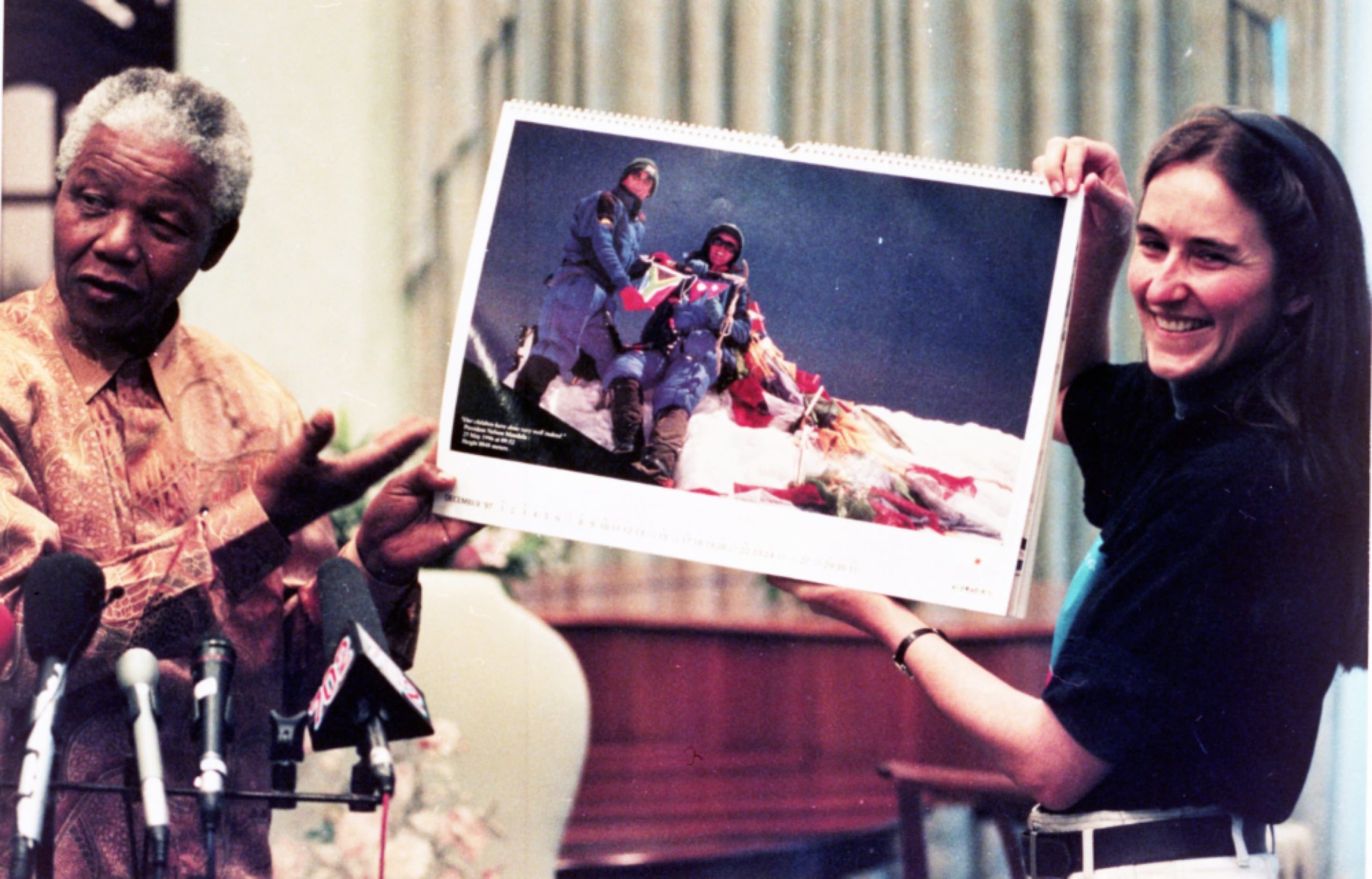

Ian Woodall (left) and Cathy O’Dowd on the summit of Mount Everest.

The photo was taken by Pemba who wasn’t paying too much

attention to holding the camera straight.

That’s it, I thought. That is the summit of Everest.

For the second time that day I was filled with an incredible sense of excitement. At last I knew that not only was I capable of climbing Everest, but that I had actually done it. Only ten more metres. I had never imagined it would get to this.

The last slog up the final slope seemed interminable. I clambered slowly towards the dash of colour, which became a pile of prayer flags covering a metal tripod.

Ian spoke into the radio: ‘And then there were three.’

Philip’s voice came through in a chatter of excitement.

I sank down onto my knees beside Ian and hugged him, barely able to feel the man beneath the piles of clothing we were both wearing. I turned to hug Pemba, acutely conscious of the pleasure of being able to share the moment with friends. I was glad that I was not there alone.

Ian had reached the summit some twenty minutes earlier, followed shortly thereafter by Pemba. He had announced over the radio: ‘We have 9:52 and the Nepalese and South African flags are flying on the summit of Everest.’

The base camp crew had broken out into wild cheering. They had begun to pass round the tins of San Miguel beer that had been chilling on the ice of the glacier. Patrick had answered the phone to find it was the producer of the Radio 702 morning news programme.

‘Hold on,’ he had said. ‘There’s a broadcast coming through, they’re somewhere on the mountain.’ Then he had begun to shout. ‘They’re on the summit! They’re on the summit! Put me on the air! Put me on the air now!’

The news had gone out at six o’clock in the morning in South Africa, to friends and family who had been awake all night, to insomniacs and early birds, to depressed rugby fans who had just watched the All Blacks thrash the Springboks at rugby.

Now Ian thrust the radio at me. Pulling off my mask, I was aware of the immediate drop in oxygen supply. There was only a third as much air here as there was at sea level. I spoke into the little black box in my gloved hand.

‘Hello, base camp, can you hear me?’

Everyone offered me their congratulations.

I sat on the pile of snow, trying to order my thoughts, trying to let the enormity of it all sink in. I couldn’t believe that I, that we, had actually done it.

Then my mother’s voice came through faintly from the black box.

‘Hello, Cathy? Good morning, darling. You are the star for us.’

How strange it was to be so far away and yet so intimately connected, to stand on the summit of the world and speak to my mother in her living room in Johannesburg. It was a huge thrill to be able to share with her the very moment that I was on top. My parents had been so supportive through all the difficulty, never hinting to me what worries or fears they might have.

I tried to sort my thoughts coherently, to be able to say something meaningful over the radio. But the emotions that were swelling through me tossed my words into chaos.

Ian handed Pemba the camera and he and I clambered onto the summit itself, holding out Ian’s ice-axe with the Nepalese and South African flags hanging from it. After weeks of battling the most ferocious winds, the breeze was now not even strong enough to make the flags flutter.

I looked down at the multi-coloured blaze of the South African flag with a shiver of excitement. I remembered being a teenager in the ‘old’ South Africa, standing in the hall of my school in Johannesburg, mouthing the words of the national anthem ‘Die Stem’ and wondering what it would be like to live in a country where one was actually proud to be a citizen, where the anthem and the flag really meant something.

And now I knew.

I never expected to do something under the colours of my country, to make any kind of public contribution to the achievements of the nation. But now as I looked down at what was for a brief moment the highest flag in the world, I was proud to be South African, and proud to have forged a small place in the history of my country.

I looked at what actually marked the summit of the world. The large metal tripod left by the Americans in 1992 as part of a re-surveying of Everest’s height was almost covered in vividly coloured Buddhist prayer flags. Beneath them was a collection of tiny photographs in frames. Although I did not know it at the time, Jamling Tenzing Norgay, who was part of the IMAX team, had left them there. He was the son of Tenzing Norgay, the Sherpa who had done the first ascent of Everest with Edmund Hillary 43 years earlier. I removed the South African flag badge that was pinned to my fleece jacket and placed it in the snow.

Part of me wanted to relax, to sit down and soak in the sense of really being on top of the world. But that was overwhelmed by the nagging worry of the long, long way we had to descend. Every one of those steps so laboriously taken on the way up still had to be taken again before we were safe again at camp. The summit was not a finish in any sense, but only a halfway point. I knew the risks of descent, the chances of making a mistake due to tiredness or simply lack of concentration. With the drive for the summit gone, all that remained to keep us moving was the survival instinct.

To spend only 15 minutes on top after months of effort to get there seemed less than logical. But in the end it had been about getting there, not about being there.