Wits University in Johannesburg was where I did my undergraduate degree and their Mountain Club was where I began climbing. This article was written for the Wits Mountain Club Journal. It mixes a description of the summit day on Everest, 25 May 1996, with some of my pre-Everest climbing.

It was the morning of the 25th May, 1996.

I stepped onto the top of the south summit of Everest. The south summit, higher than any other mountain in the world, higher than K2, it’s not a bad achievement, I told myself. But could I go further?

I looked onto the ridge that ran towards the true summit. In a few shocked seconds I absorbed several salient facts. It was a classic mountain ridge, knife-edged, corniced, twisting gently up over a series of rises. I instantly recognised the rock step on the ridge as the Hillary Step and realised that it wasn’t as fearsome as I had imagined. I noticed the doll-like figures of Pemba Sherpa and Ian Woodall approaching the step, and saw they weren’t as far ahead of me as I had feared. I took in the knife-edged nature of the ridge and the immense drops on either side of it and dismissed them as doable. And I realised that although the summit was still not in sight it could not be too distant.

From deep within me incredible excitement began to well up.

I can do that, I thought, I can climb that ridge. I have the energy and the ability. For the first time in the entire expedition standing on the summit of Everest manifested itself for me as a concrete possibility, rather than just a wishful daydream. All the weeks of uncertainty, of bad weather, of ill health, were swept away in the awesome realisation that the goal lay so tantalisingly close.

It was ten years and half a world away from orientation week at Wits in 1987. I knew then I hated all physical activity, or what I knew of it in the form of school sport. Nevertheless, I enjoyed the outdoors. I had spent the week wandering around the university, looking at all the clubs on offer. I had watched with disbelief the figures in old khaki shorts and shocking pink lycra scaling the library wall, and listened to the pitch from the Mountain Club chairman. I was not convinced, and was more interested in joining the Exploration Society. But on the very last day, with the abandon born of spending my father’s money, I decided to join the Mountain Club as well.

Crossing the ridge was slow, cautious work. The trail ran just to the left of the knife-edge of the ridge, staying below the cornices which hung over the Tibetan side, while staying above the unstable dinner plates of rock a few feet down on the Nepalese side. The only flat ground was the footprints left by previous climbers. I moved up the ridge almost as if I had put on mental blinkers, seeing only the two footsteps ahead of me. With each step I sunk the shaft of my iceaxe into the snow on the uphill side, using the head of the axe to provide a handhold. It was, I thought, a little like walking along an undulating plank. Not particularly difficult, as long as you ignored the fact that there was an 8000 foot drop on the one side, and a 10 000 foot drop on the other.

As a teenager even cable cars and glass-faced lifts frightened me. One classic epic in my second year of climbing started on Boggle, 19, in Cedarburg. Following the overhanging jam crack that comprised the third pitch blew my mind. Terrified of swinging out into space if I fell off, I burrowed into the crack, refused to move in any direction, and burst into tears. The leader, with infinite patience, slowly coaxed me up, move by move. I rewarded that patience by finally clawing my way over the top of the cliff and absolutely refusing to do the 50 metre free abseil back into the kloof. To return to our campsite at the top of Boulderkloof he and I were forced to walk all the way up to the crossing at Upper Tonquani, and back down to Boulder, much of it in the dark, without headtorches.

My steady progress along the ridge was broken by the sudden rock wall of the Hillary Step. I stopped short, trying to refocus mentally from snow to rock. The first section was relatively easy, involving some cautions scrambling up and round big blocks. Then a cautious traverse across loose scree brought me to the foot of an awkward, angled chimney. The floor was loose rock and snow, the chimney just wide enough to wriggle up with a pack on. I worked my way up it, suddenly conscious of the burden of the bulky clothing, the big oxygen set, the enormous boots and crampons. Jammed awkwardly near the top I contemplated the tangle of ancient fixed rope that hung down the back of the chimney. The creeper-like mass consisted of bits of all sizes and colours, much bleached bone white from years of extreme weather. Manoeuvring past it without getting it tangled around my rucsac, crampons or iceaxe was a much of a challenge as negotiating the wall itself. Finally I grabbed a huge bundle of it in one hand and pulled, wriggled and flopped my way onto the summit of the block.

The first rock climb I ever did was Donderhoek Corner in Upper Tonquani, all of grade 12. A classic chimney thrutch, it was an unprepossessing beginning. The second was Hawk’s Eye, a daring 13. Although I coped well with the wall, it took quite some talking to get me to climb over the nose of the hawk’s eye. I quite enjoyed the climbing, was less impressed by the amount of flaming Sambuka being thrown down everyone’s throats, and was far from convinced that this was an experience to be repeated. However, I was impressed by a young and handsome blonde called Mike Cartwright. And given that the only place he could be found on the weekends was in the kloofs, I decided to give this climbing lark another go.

I realised with amusement that although the exposure, and the danger, was far greater here than on the slopes lower on the mountain, I felt no fear, only exhilaration. I could see straight down the south-west face of Everest into the Western Cwm, down to the tiny campsite over 2000 metres below me, our Camp Two. We had come a long way since then, and a longer way still from home. Months of planning had been followed by two weeks of walking just to get to the mountain. And we were now into our ninth week on the mountain, and our third attempt to reach the summit. The first two attempts had been halted by storms. Already ten people had died attempting Everest this season. All the other expeditions had left for home, many without summitting. The monsoon storms were only days away. This was the very last chance to reach the summit.

My first great pronouncement on my climbing career was made half-way up a chossy 13 at Wilgepoort when I declared to my fellow follower, Linda Waldman, that while I liked climbing, I had no interest in leading. She agreed. Within a few months we were both leading, and within a few years, I joined Michelle Smith as one of the only two women in South Africa to have led a 23.

My next great pronouncement came after Mike hauled me up Last Moon at Blouberg. The first six pitches I had enjoyed, but then I was ready to go home. Unfortunately we were only half way up. I declared myself a cragrat, interested only in walk-ins under half an hour, and climbs of two pitches or less. Over the next few years I climbed big walls all over the country, from Blouberg, to the Drakensberg, to the Western Cape, and then moved onto 600 metre rockwalls in the Alps.

My third great pronouncement was that, although big walls were great, you wouldn’t catch me dead mountaineering. Too high, too cold, too dangerous….

I had been moving alone along the ridge for a long time. Pemba and Ian were out of sight ahead of me, the other three climbers somewhere behind. Although I mostly restricted my concentration to the few steps in front of me, blocking out the vast empty spaces that surrounded the ridge, occasionally I allowed myself the luxury of looking out across the myriad of snowy peaks below me. With no other people in sight, and no signs of human existence visible below it was like being the last person alive on earth.

Hundreds of mountains stretched off in every direction. On one side, I could see down into the Kangshung glacier. The barren plains of Tibet were bordered by the sweeping arc of the Himalayas. The giant pyramid of Makalu, fifth highest mountain in the world, dominated, while the brooding hulk of Kangchenjunga, third highest, sat on the distant horizon. Behind me stood Lhotse, fourth highest, whose huge south-west face we had toiled up so many times on the way to our fourth camp. Behind that was the valley we had walked up so many weeks ago, and the myriad of smaller peaks that made up the Nepalese Himalayas. On the other side the Himalayas stretched away again towards Pakistan, with the green plains of India visible beyond them. The squat form of Cho Oyu, sixth highest, and the only other 8 000er climbed by South Africans, commanded the view.

My first encounter with snowy peaks had been in the July vac when I went to the Ruwenzori in Central Africa. As we approached the mountain, concealed in cloud, the glaciers and rock peaks appeared suddenly out of the swirling mist, like a divine revelation. I was hooked. Stephen Kelsey and I spent two weeks climbing every summit in the range, not seeing another person in all that time.

The following July vac, for the second year running, I convinced the History Department to allow me to write delayed exams. I headed for Bolivia, for my first encounter with a real mountain range, the Andes, and with real altitude, up to 6000 metres. I haired up the mountain, trying to keep up with the boys, and promptly went down with altitude sickness. I watched, I learnt, I got cold, tired and frightened and I loved every minute of it.

I swotted for the history exam on the plane back from South America. When I bitched to one of my History professors that I never seemed to quite crack firsts, he told me dryly that if I could bring to my History the passion I expended on my climbing, I would have no problems.

Once above the Hillary Step the ridge widened slightly. It was still corniced and very steep on the Tibetan side but slightly gentler on the left, before the steep drop of the south-west face. It undulated gently, resulting in a long series of false summits. Each crest looked as if it might be the final one, but as I dragged my weary body onto the top I would find another one slightly higher, slightly further on. The ridge seemed to run on interminably in front of me. I felt as if I might be on a snowy treadmill, a ridge that ran for ever with no conclusion, and I condemned to walk it for eternity.

I had anticipated the false summits, remembering reading about them in Stacey Allison’s account of the first American female ascent of Everest. I tried to suppress all expectations, to simply deal with the ridge step by step, rather than face of inevitable disappointment that expectation of the summit would bring.

The first mountaineering book I had ever read had been at the end of my first year of rock climbing. Mike, myself, and most of the Witsies had decamped to a flearidden flat in Fishhoek, to sample the delights of Western Cape climbing. We grovelled up Jacob’s Ladder and Cableway Crag on Table Mountain and accounted ourselves heroes. We scared ourselves silly climbing Energy Crisis at Wolfberg and realised we had a lot to learn still. And, to pass a rainy day, I raided the Fishhoek library and found a book about an all-women expedition to Annapurna.

I was fascinated by the concept of the challenge, and by the realisation that it was not just a man’s world. Although not yet believing I could do such a thing myself, the first seed of my captivation with mountaineering had been planted. Some time later I sat in fascination once more in Senate House Basement, listening to British mountaineer Stephen Venables tell the story of his ascent of Everest, the first British ascent without oxygen. This caught my attention far more than any English lecture in the same venue ever had.

When I left Wits at the end of 1991 I had a degree in History, History of Art and Classical Civilization. I’d had great fun getting it but had no idea what to do with it. I dithered between honours in History and a year climbing in Europe. Not a hard choice to make, I spent the British winter selling climbing equipment in London and the next summer camped in the French Alps. I travelled alone, finding partners as I went, climbing bolted rock in the south of France, huge granite faces above Chamonix, frozen waterfalls in Switzerland, rock, ice, snow, mixed. And everywhere people spoke with awe of the distant Himalaya, of the great mountains of the world.

I moved slowly up yet another small rise and onto the top of it. And stopped short, aware of two figures and a sudden blaze of colour. Ian and Pemba were seated in the snow with something behind them that to my puzzled gaze looked rather like a ruined tent. After hours in a virtually monochrome world of blue sky, white snow and black rock the medley of red, yellow and green was disconcerting.

Then Pemba turned and saw me. As a huge grin spread across his face, he stood up and began to wave both arms and his iceaxe in the air.

That’s it, I thought. That is the summit of Everest.

For the second time that day I was filled with an incredible sense of excitement. At last I knew that not only was I capable of climbing Everest, but that I had actually done it. Only 10 more metres. I never imagined that it would get to this.

The last slog up the final slope seemed interminable. I was very tired, stopping to rest every four or five steps. I walked slowly towards the blaze of colour, which resolved itself into a pile of prayer flags covering a metal tripod.

Ian spoke into the radio: “And then there were three.”

A ragged cheer came over the radio from base camp.

I had reached many summits over the years – up the south-east arête to the summit of Sentinel in the Drakensberg, jumping on top of the summit cairn to feel my hair standing on end from the static of the electric storms; on the summit of the granite monolith of Spitzkoppe in Nambia, to stare over miles of desert; on the summit of Monteseel, all of 10 metres higher than where I had started; on the summit of Mont Blanc du Tacul in the Alps as the sun rose. And I had failed on as many in those years. Turned back from the Western Injisuti Triplet in the ‘Berg by driving rain; hopelessly lost in the mists of the Ruwenzori; retreating from tottering choss on Illampu in the Andes.

I sunk down onto my knees beside Ian and hugged him, barely able to feel the man beneath the piles of clothing we were both wearing. I turned to hug Pemba, acutely conscious of the pleasure of being able to share the moment with friends and team mates.

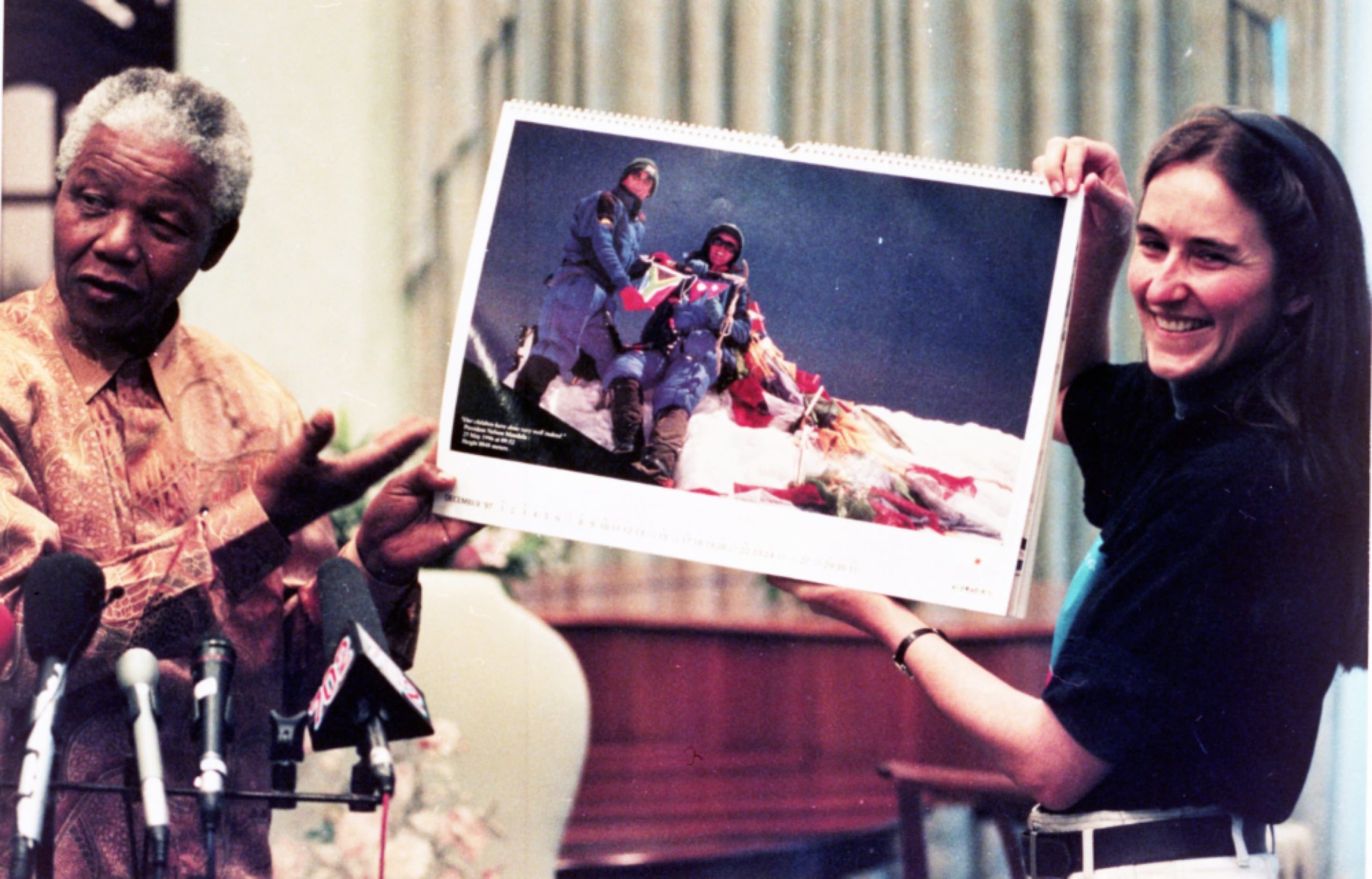

Ian handed Pemba the camera and we clambered onto the summit itself, no bigger than a table top, sloping gently and then increasingly steeply down on all sides. We perched next to the tripod and flags, holding out Ian’s iceaxe with the Nepalese and South African flags hanging from it.

I looked down at the multi-coloured blaze of the South African flag with a shiver of excitement.

Long ago I had stood in my school hall, mouthing the words of Die Stem and wondering what it would be like to live in a country where one was actually proud to be a citizen, where the anthem and the flag really meant something. As the years passed I experienced the frustration of a country that seemed as if it would never change, the fear and adrenaline of Wits students taunting the riot police, the despair of my male climbing friends as they sought way to avoid army call-up, either in endless further degrees or in skipping the country.

The changes in the country are all linked in my mind to climbing. I came down from climbing Mpongwane to find the ANC had been unbanned. On the day Mandela was released I was on a train back to Rondebosch after a day of climbing on the Lion’s Head Granite with Linda. In the excitement of reading the news reports we missed our station and landed up in Muizenburg.

As I looked down at what was for a brief moment the highest flag in the world, I was proud to be South African, and proud to have forged a tiny place in the history of my country. Although the three of us seemed so alone on that summit, back in Gauteng thousands of South Africans were listening over Radio 702 as I spoke from the top of the world to my mother in her Johannesburg living room. That summit was the result of help and support from people all over Nepal and South Africa.

We took the South African flag down with us, to return to President Mandela, who, as our expedition patron, had given it to us. But I was reluctant to leave no trace of South Africa’s brief passage across the top of the world. I took the South African flag badge that was pinned to my fleece jacket, and placed it in the snow. A tiny bit of South Africa still lies up there somewhere.

Yet the expedition was not over. Every step taken on the way up had to be taken again on the way down before we were safely off the mountain. I knew the risks of descent, the chances of making a mistake due to tiredness or simply lack of concentration. With the drive for the summit gone, all that remained to keep us moving was the survival instinct.

As we moved down the ridge we passed the body of New Zealand expedition leader Rob Hall, one of the victims of the great storm of two weeks previously, where eight climbers had lost their lives, while we had been pinned down in our Camp Four, at 8000 metres.

I stood by him for a few minutes, a tiny personal tribute to the life, the achievement and the tragic death of this talented climber. It was so strange that we could be both be climbing the same mountain and yet have such radically different experiences.

We crossed slowly over the south summit and down onto the steep ridge below. We passed Ang Dorje Sherpa and Jangmu Sherpa, who went on to reach the summit an hour after I had. Then Bruce Herrod, the expedition photographer, became visible below us, moving up the steep ground above the rock step. As we balanced precariously on the ridge he pulled me into his arms for huge bear hug. He was so pleased that we had done it, that following the weeks of work that we had all put into the enterprise, the expedition had achieved its goal. We suggested he return with us, but he was adamant that he wanted to go on. With perfect weather, plenty of oxygen, a radio, many hours of light left, it was not an unreasonable decision. After extensive discussion we wished him luck and he went on up.

Bruce called us from the summit when he finally reached it. The joy and pride in his voice was all we had to carry with us in the long hours that followed, as we waited for the return that never came. Bruce vanished on the summit ridge of Everest.

Like all beginners I had spent the first months of my climbing career assuring my parents that this was a totally safe sport, and they need have no worries. The years that passed revealed the lie behind that. I remember the day that Grant Murray, climbing on the OMSH wall to demonstrate to Orientation week beginners how safe climbing was, tried to lower off on his gearloop. It broke and as he crashed into the floor his ankle broke as well.

As the years passed a succession of lives were given up to the challenge: Gill Graafland, Martin Seegers, Deiter Lubber, Dave Cheesemond, Erwin Muller, Phil Lloyd, Bev Opperman, Greg Lacey.

I remember the the phone call that told me my two climbing partners from the Bolivian Andes expedition, Stephen Kelsey and Graham Whittaker, had died together on a mountain in Peru. I nearly gave up mountaineering then, to return to my rock-climbing roots. No summit can be worth a human life. But why then do we not stay at home? Why not avoid all of the many risks involved in climbing? In the end I realised that sometimes it is the risks that make life worth living, that bring us an intensity of experience that no amount of Johannesburg suburbia ever will.

In the two long days of climbing that followed to get us and all our kit down to the safety of base camp, emotions oscillated like a rollercoaster. The triumph and the tragedy swirled round each other as we sought to find a perspective on the experience. The friendships made on the mountain carried us through the strain of the criticisms that enveloped us from the arm-chair critics.

As the small group of people that had made up the First South African Everest Expedition walked down the Dudh Kosi valley, between some of the great mountains of the world, we were already discussing future possibilities, other expeditions.

On 25 May 1995 Ian Woodall, Pemba Sherpa, Cathy O’Dowd, Ang Dorje Sherpa and Jangmu Sherpa reached the summit of Everest on the First South African Everest Expedition. Nawang Sherpa reached 8000 metres and Deshun Deysel reached 6500 metres.

This article appears in edited form in the Wits Mountain Club Journal 1996.