Pemba’s headlight wavered weakly in the inky darkness. The snow glittered in its beam, the surface deceptively crisp. Once more he stepped upward. Once more the surface broke and he sank down to the thigh.

It was 2.30 a.m. on 26 May 2000. We’d been climbing for less than twenty minutes and were standing at just over 7 900 metres on the slopes of Lhotse, at 8 516 metres the world’s fourth highest mountain. The portents were not good. The batteries of my headtorch were dead and my spares had vanished. By bizarre coincidence, Sandy’s headtorch had failed just minutes after mine. Only Pemba’s was working and he, like us, was mired in soft snow. It looked as if our summit bid on Lhotse was over before it had begun.

The night was clear and to the north I could see tiny headlights, like fallen stars, wending their way up the summit pyramid of Everest. As I watched two peeled away and began to descend. This late in the season there would be no chance for another try. I wondered who they were. I wondered if they would look across and see our little light descending too. It was not a good year in the high Himalaya.

Lhotse had first entered my consciousness in 1996 as simply another obstacle on my ascent of Everest. The 1800-metre-high west face of Lhotse is an endless icy treadmill between the western cwm and the south col, home to the final camp on Everest.

On 25 May 1996 I reached Everest’s top. For nearly three hours thereafter I carefully descended the knife-edge summit ridge, climbing straight towards Lhotse’s west face. The ice of the face is surmounted by a vast coronet of black rock, steep, jagged, loose, well over 8000 metres, and by current standards unclimbable.

However, straight up through the rock runs a couloir, arrow-straight, ribbon-thin, heading directly for the summit. It is the perfect pathway to the top, the only straight-forward route up the mountain.

The south face has only had one undisputed ascent. The east ridge, with its prize of Lhotse Middle, the world’s highest unclimbed peak, has resisted attempts for decades. The north face is just so wild no one even talks about it.

But the couloir is classic in its perfection. It had had its first ascent by a woman just two weeks before, when the French climber Chantal Maudit reached the top on 10 May. The image of that icy ribbon stayed with me over the years. In 2000, when I finally returned to climb it, still only three women had reached Lhotse’s summit.

Spring 2000 had proved a wild and stormy season. A massive American Everest clean-up expedition had sat idle right through April because the South Col was so deep in snow that they couldn’t find any oxygen bottles to remove.

Sandy pushed past the now exhausted Pemba and moved up and leftwards in hope of firmer ground. Now he was only sinking in to the knee. We would not be giving up just yet.

We were only days away from the end of the season and the break-up of the route through the Khumbu icefall. Many climbers such as Sandy had been mooching about on Everest and Lhotse since late March. Most had given up, drained by exhaustion, boredom and discomfort. I had received disbelieving looks when I waltzed into base camp on 7 May, the very last climber to arrive.

It was a calculated gamble. My summit bids on Everest in 1996, 1998 and 1999 had been on 25 May, 24 May and 29 May respectively. I believed there was a window of good weather in the last ten days of May. Nor had I wanted to waste weeks in acclimatization at base camp and through the notoriously risky Khumbu icefall. I chose instead to spend two weeks climbing Mera, at 6 476 metres a straight-forward but spectacular peak just east of the Khumbu. A custom trip for clients, they set the pace and sadly one reached the end of his strength after a night at 5 700 metres. We all turned back with him.

On arrival at Lhotse, I did one day trip up to the top of the icefall, and then pushed straight to Everest’s Camp 2 at 6 500 metres, where I stayed for the next two weeks.

The Khumbu icefall is a 1000-metre high rapid of ice that tumbles down the narrow chasm between Everest and Nuptse, a maze of towering blocks teetering over bottomless crevasses. Inching slowly downward, its character changes over time and it was distinctly different from 1996. Crevasses were fewer and narrower, the ice blocks more stable. It is as if the icefall is slowly falling in on itself, gradually solidifying. One classic horror remained, though, close to the top. A vast crevasse lay before a three-storey-high ice wall. The feature was surmounted by five ladders tied end to end. As the crevasse steadily widened, the web of ropes holding the ladders in place tightened. The ladders were pulled up from the snow, balancing in air, bouncing and twisting with every step.

The snow field was narrowing above us, gradually funnelling down to form the famous couloir. Grey masses of form were beginning to appear out of the darkness. Being on the west face, we had no hope of sunshine but just being able to see would be a boost to morale. Gradually the distant peaks of Shishapangma and Cho Oyu were becoming visible, pale pink peaks against a grey blue sky. The western cwm remained veiled in shadow, cradled between the sweeping arms of the Nuptse ridge and the west ridge of Everest, one a wedding cake ridge of ice, the other a black forest gateau of snow-streaked rock.

The climbing remained challenging. The ropes fixed by the Russians were buried. We were climbing solo and the unstable snow made it a treacherous business. Just turning out to look at the view took care. I felt guilty about stopping to take pictures, afraid of wasting precious time, worried by how far ahead Pemba and Sandy seemed to be. Yet I knew I would only be here once, watching the eastern edge of the summit pyramid of Everest glowing gold in the light of the rising sun. I could take a moment to savour it.

I was somewhat intimidated to be in the company of Scottish mountain guide Sandy Allan. He had been on two of the British expeditions in the 1980s which attempted the ‘last great problem’ of Everest, the north-west ridge. He was now climbing Lhotse in his holidays, so to speak.

Sandy, like myself, fell under the umbrella of Henry Todd’s Lhotse permit. I had my own team-within-a-team, with tents, food, and Sherpa support. Pemba Sherpa, who had reached the summit of Everest with me twice, was now hoping to get his first ascent of Lhotse. Sandy, without this kind of support, was rather out on a limb, with Henry concentrating on his Everest clients. Sandy happily joined up with me and Pemba. He was a charming companion and turned out to be a welcome third set of legs for breaking trail.

A strong Russian team were trying for an ascent of Lhotse Middle. They were a charming lot, constantly giving me tins of salmon caviar. However, two of their members were buried in a slab slide at their 7300 metre camp and were lucky to be dug out alive. One survivor had a massive gash in his forehead where he had been hit with a snow shovel. After imbibing vast quantities of vodka to calm their nerves, they did a quick ascent of Lhotse and headed home.

We were now fully within the rock walls of the couloir. My first goal had been reached. During the unstable weather of mid-May we made one attempt but pulled out after a windy night at 7 400 metres. I decided then that come what may, I would not give up until I stood within the walls of the couloir.

Cathy at Lhotse camp 4, 7900 metres.

Pemba descending the Lhotse coulouir.

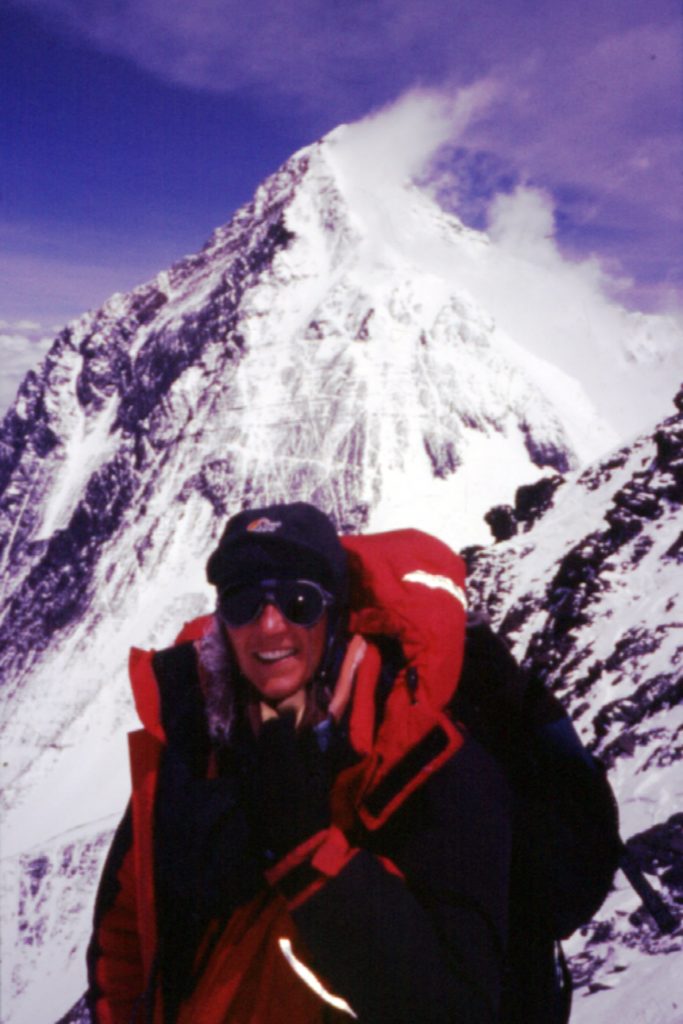

Cathy on Lhotse with Everest behind.

The couloir was very much an unknown quantity, because its condition varies so much year by year. American climber Christine Boskoff, who in 1997 made the second female ascent, told me that then the ‘bottle-neck’ of the couloir had beem so narrow that she had to bridge up on the rock. Yet as I climbed the couloir was never less than three metres wide.

Christine was back in 2000 to try Everest, her climbing partner the famous Peter Haebler. Twenty-five years earlier Peter, along with Reinhold Meissner, made the first ascent of Everest without oxygen. Now he was back, having apparently promised Reinhold that he would not use oxygen. After having reached the South Col three times, he finally gave up. Christine grabbed some bottles of Os, and reached the top. Climbing the west face of Lhotse is great fun. On one hand you have all the pleasures of the modern Everest social scene. And it is a great social occasion, with famous climbers from all over the world hanging out together for two months.

Dawn had unfortunately brought us bad weather. The clear night sky was now covered in scudding cloud. The wind was whistling up the face and being channelled into the couloir. It came howling up behind us, bringing freezing temperatures and fountains of spindrift. Everest has disappeared in a veil of shifting cloud. Lhotse’s summit had vanished into grey mist. I had no idea how high we were.

We had known we risked bad weather. My theory of the late weather window was not being borne out. However, running out of time, the previous day we had moved with Henry’s Everest climbers up the Lhotse face, and across the yellow band. Where they continued on a rising traverse to the Geneva Spur, we struck out straight up, heading for a rock blob nicknamed the turtle shell. The rock shelves at 7900 metres provided the only point high on the west face where tents could be pitched. There we had huddled the previous evening while I checked the connections on all the oxygen bottles, the vital bottled air that would take us into the infamous ‘death zone’.

Now as I felt a suffocating hand tightening round my throat I realised my bottle was empty. Done methodically, it should only be the work of minutes to change to a fresh one. But the new bottle wasn’t catching. I stared into the regulator. The tiny metal valve was tilting loose and was soon made worse by having snow from my gloves mixed into the system.

The metal valves are the niggliest link in the system, as they have to be set just right to connect with the pin in the oxygen bottle. I needed a penknife. In my minds’ eye I could see it – lying in the pocket of the tent. I had been using it the night before and in the foggy confusion of midnight waking and packing, forgotten it.

Without oxygen I doubted that I could tackle the upper section of the couloir, both the climb up and the equally tricky descent. It looked like my climb might be about to reach an inglorious end.

Pemba’s penknife solved the problem, although not before my fingers were completely numb. I shoved them into my armpits and rocked back and forward as icy hot aches shot up my forearms. With half-feeling fingers I swung my rucksack up onto my back and resumed the slow climb upwards in Sandy’s footsteps.

Finally I noticed he had moved onto the steep rock on the right. The couloir seemed to reach an end above us, and on either side stood a peak, the right one all rock, the left an easier rock-and-snow mix but further away. The twin peaks of Lhotse. Now which was higher?

Standing below them, mist swirling round us, it was impossible to tell. I tried to remember climbers tales. I thought Christine said she had gone left, but then didn’t the Russians say they went right? Or was it the other way round?

Pulling off my oxygen mask, I yelled up at Sandy: ‘are you sure?’

‘Yes, this is right. There’s fixed rope here, and prayer flags above me,’ he replied. ‘Besides, this is more interesting climbing.’

‘Too dangerous, too dangerous,’ muttered Pemba. ‘Go left. Summit left.’

Now did he really know that or did he just not want to tackle the rock? And was Sandy really sure or was he just following a climber’s nose for the hardest route? I tossed a mental coin and followed Sandy. I had no idea if he was right but the idea of trying to climb steep rock at this altitude intrigued me.

The climb was difficult, endless broken ledges sloping downwards, no solid edges for mittened hands to grab. My crampon points skittered dangerously across the smooth rock. Sandy climbed on slowly above me, while yelling down random bits of advice, most of which I could not hear. Pemba would have nothing to do with it and slogged off through the snow towards the other peak. I joined Sandy at the prayer flags, looped round a giant boulder. A few metres above us the rock ended in a rail of ice. By now the mist was thick around us. Pemba, the other peak, the Himalaya, had all vanished. We could have been on a Scottish peak, or the Drakensberg escarpment, for all we could see.

We edged up the last few metres, and I gingerly grasped the ice rail in both hands and looked over. An ice face dropped dizzyingly into a misty oblivion. To our right ran the ridge towards the much-desired Lhotse Middle. It was a wild crest of snowy cornices and icy knife-edges. Frankly, the Russians could have it.

It was 9.45 a.m. We spoke briefly to base camp on our radios and were told that some of our friends on Everest has made it. Pemba’s voice broke through on the radio. He too had reached a summit somewhere out there. We took a few pointless pictures of mist and turned away.

The scramble down the rock was slow and precarious. For a few minutes we debated climbing the other peak, but inertia, exhaustion and fear of staying high too long all combined to drive us on downwards. The couloir seemed suddenly steeper as I descended facing outwards. I was horribly conscious that it was 2000 metres down to the western cwm, a long, long way to roll.

The mist shifted to provide glimpses of the slopes of Everest and of the myriad of peaks beyond. It had been a pushy ascent, with great companions and a happy ending. Now other possibilities spread out tantalizing below me – so many mountains. But for the moment my eyes were focused on the distant valley and the comforts of camp, a square meal, a good night’s sleep and then the start of the long trail home.

In retrospect, looking at pictures of Lhotse seen from Everest, the peak that Pemba climbed is probably higher by a few metres. According to the Himalaya’s ‘keeper of the records’, Liz Hawley in Kathmandu, everyone always claims to have climbed the highest peak, whichever that may be, which means that if we did indeed climb a slightly lower peak, it will have been a first ascent. Of course the fixed rope and prayer flags indicate that it is not.

January 2001

This article appeared in edited form in the Mountain Club of South Africa Journal 2000.